Novel (2023)

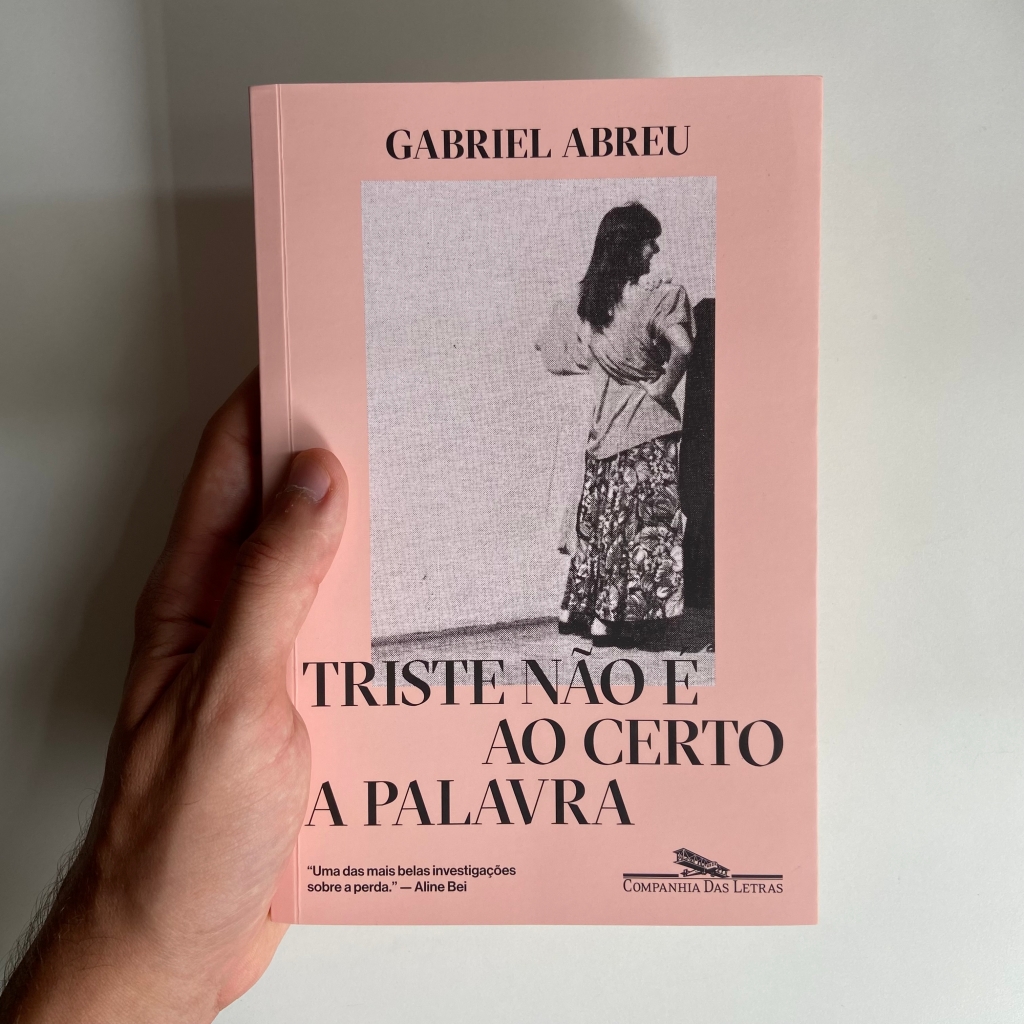

Sad isn’t quite the word (Triste não é ao certo a palavra) is Gabriel Abreu’s first novel, published in April 2023 by Companhia das Letras.

About the book

A mosaic that goes beyond the narrative form to create a delicate yet fierce portrait of legacy, memory and love in a relationship between mother and son.

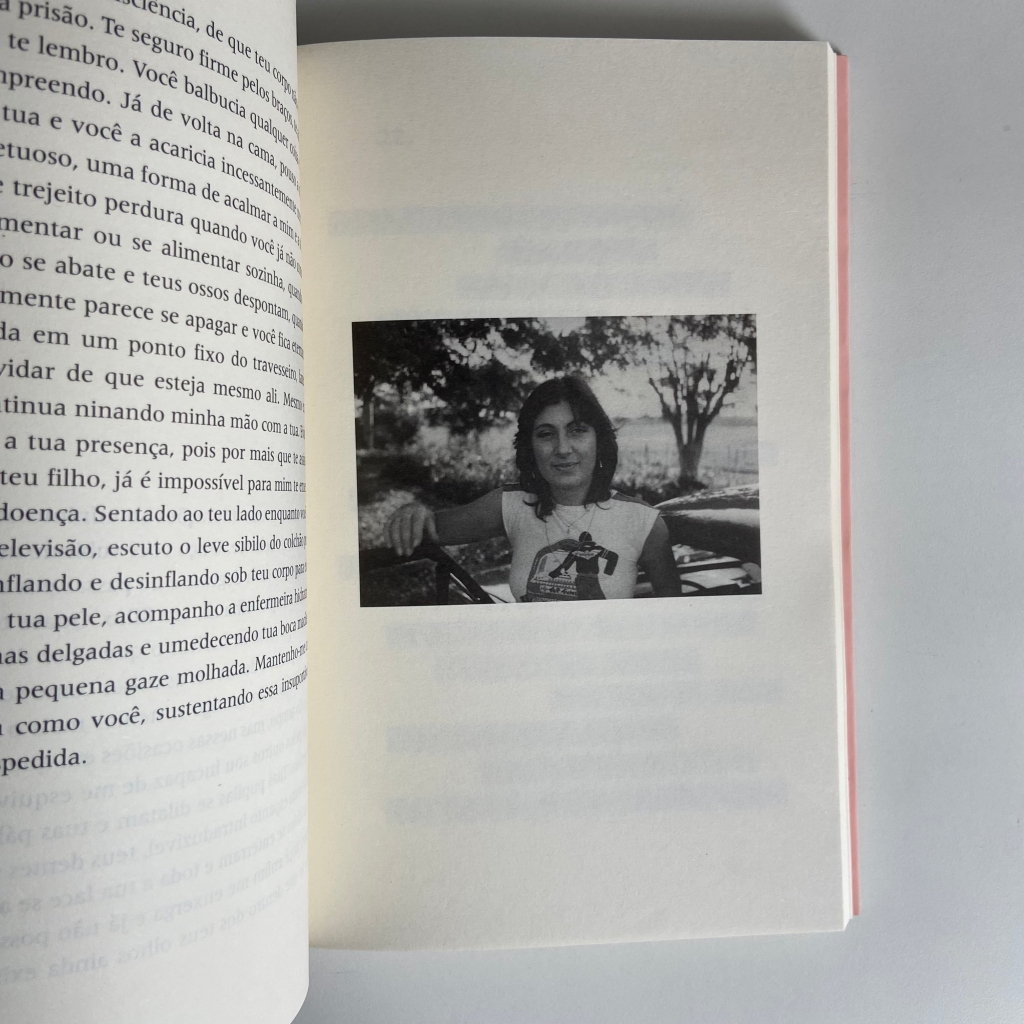

A diary, hundreds of photographs and sixty-eight letters are all that G. has of his mother, besides memories of a shared past. The cardboard box that contains all these elements also carries the expectations and anxieties of a son trying to build his own identity and recover a contact that is no longer possible.

As he goes in search of this woman – of who she was before motherhood, of the mother who was born with him, of the mysteries of individuality –, G. investigates medication package inserts, medical diagnoses, astrological charts. He rewrites letters and emails. He probes himself and concludes: “I write and send you this letter to try to rediscover, in my voice, your own.”

In this sensitive and daring debut novel, Gabriel Abreu assembles an exciting puzzle of records, affections and memories that only a son on the verge of losing his mother can.

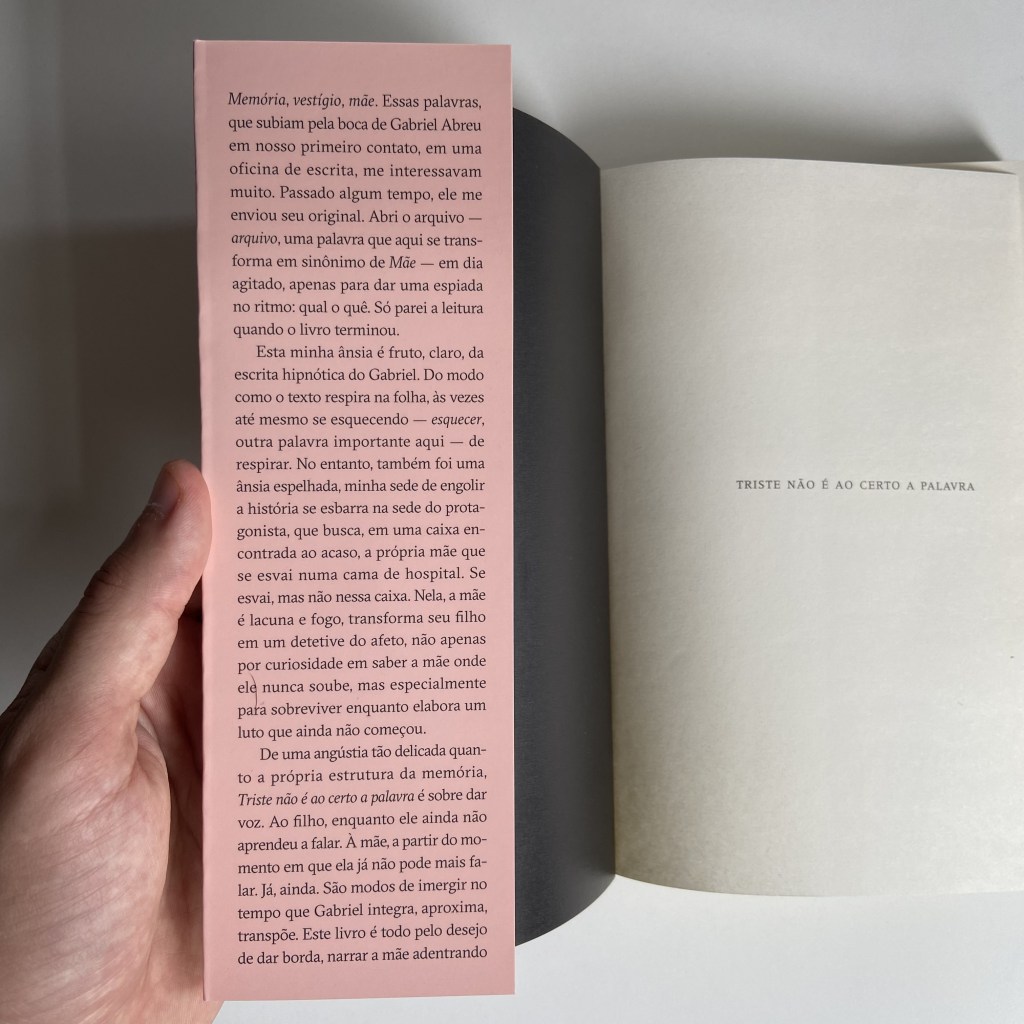

“From an anguish as delicate as the very structure of memory, “Sad isn’t quite the word” is about granting a voice. To the son, while he hasn’t yet learned how to speak. To the mother, at a time she is already unable speak. Already, yet — ways of immersing oneself in time which Gabriel integrates, approaches, transposes. This book is driven by the desire to draw a border, to narrate the mother by the use of her archives is a lyrical strategy to make the mother possible, continuously. One of the most beautiful investigations into loss.” – Aline Bei

“In this book, Gabriel Abreu invents a new language, that of unspeakable feelings. A unique book, written by a rare observer of human emotions.” – Juliana Leite

Book excerpt

The notebook at the bottom of the box almost comes apart at my touch. I carefully remove it and notice that the old leather cover is peeling off in several places. The pages have that familiar aged paper look, with a more yellowish tone and small brown spots. I recognize your handwriting. Letters formed geometrically in a style befitting your profession as an architect. I read the first note: I was born at 9:15 pm, weighing 3.65 kg and measuring 50cm. It’s a diary, a diary of my first year of life. I scan this and other entries on these pages made pale by time. The record of the first time I smiled, of a tooth that came out too early, of the doctor who said I’m in the ten percent of tallest babies born in the country. The words are yours, but I’m the one speaking. I’m the one describing all the firsts, recounting all the details of the story like a character-narrator. I’m the protagonist, but you’re the one writing it. In this secret correspondence in which mother and son give voice to each other, you evoke my first subjectivity and I, your new maternal identity. I read my own memories and I think I can hear you, as if you were talking about me, to me, from me, as if we still inhabited the same body. I read and I think I can hear your voice (slightly nasal, the rhythm calm, the timbre sweet, the accent never discernable to me, the first thing noticed by others). I read and decide to repeat the story. I write to restore the speech that you have lost. I write because I believe that the person here is no longer my mother and because from here I can no longer see the intersections between your body and your mind. Today’s body is an assisted, passive body, a body that is forcibly fed, cleaned and exercised. I write because your mind remains in the memory of others and today it only manifests in remnants, like the rare occasions when you smile and I wonder if it’s the last time. Or how, when you still walked around the house in the afternoon, you would stop at the door to my old bedroom and cautiously peer inside, in search of some recollection. In some secluded corner of memory, you knew what had happened there, you sensed that in that small space you had watched your child grow. But with the same casualness with which you looked, curious, for something that belonged to you, you would quickly abandon that fruitless search and continue on your vague way. I write and I send you this letter seeking to retrieve a faded personality. Who are you? Or perhaps already, who were you? Are you defined by your sanity, by your mental faculties, your profession, your role as mother? Or just you, sitting here, looking at nothing, at everything, like a child who, like me, has just been born? I write to say that I found the notebook in the box at the top of the bookshelf and that I still remember you. That you survive, even if you don’t know it.

In another line of the old diary, I find: I’m such a clever little boy, it’s like I’ve begun to discover the world in the last few days. I understand everything people say to me, if I don’t know something you just have to show me and I’ll never forget it. I talk a lot, a language only I understand. I wonder if you really didn’t understand this language of mine. If, as you recorded my discovery of the world, you were unable to hear my voice in yours. If today this common language might be our only possibility for dialogue. I write and I send you this letter to try to rediscover, in my voice, your own.

Buy the book

Website Companhia das Letras

Amazon

Reviews

For reviews in the press, see Press